This summer, a bombshell dropped amongst the college community. However, it didn’t come in the form of a summer blockbuster or Pharrell Williams track.

On the day before Independence Day, education journalists across the state received notifications of an important press conference that would be held in mere hours. City College of San Francisco—the largest community college in the world’s largest college system—was set to lose its accreditation in July 2014.

Though the conference came as a surprise, the decision did not. Like the once independent Compton College (now an El Camino satellite campus), the Accrediting Commission of Community and Junior Colleges had cited CCSF’s poor fiscal and administrative practices in several previous reports before the revocation.

AdvanceEd.com, a research-based accreditation website, describes accreditation as a process that “examines the whole institution—the programs, the cultural context, the community of stakeholders—to determine how well the parts work together to meet the needs of students.” Basically, it’s a pass/fail exam for schools. Pass, you can teach. Fail, and you lose the right to receive and offer federal financial aid to students.

For a college of 80,000, it’s a death knell.

While Compton College students were offered on-campus courses for credit from neighboring schools prior to partnering with El Camino, CCSF has no such plan in place.

Students who have completed 75 percent of their studies will be entitled to receive a degree or certificate from the college, but the remainder “would have no other option except to transfer to another accredited institution,” according to CCSF’s closure report submitted to the commission. Contra Costa College is the easiest comparison in terms of size—but it’s a 30-minute drive away and serves 30,000 fewer students than City College.

The ACCJC is the professor giving CCSF a failing grade in this case. It’s one of three accrediting branches of the Western Association of Schools and Colleges—one of the six nationally recognized accrediting bodies. Every six years, schools are required to go through the process of renewing accreditation.

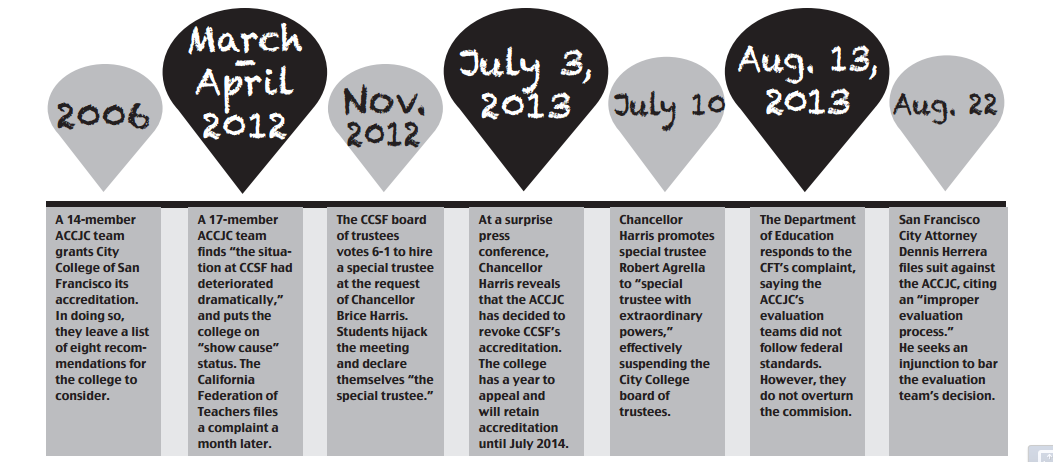

In 2006—the same year Compton College lost its accreditation—the ACCJC granted it to CCSF. But a 14-member accrediting team left behind eight “recommendations” for the school in areas they believed could become troublesome if unaddressed.

Flash forward to 2012, when a 17-member accrediting team found the situation had further deteriorated. CCSF was placed on show-cause status, meaning the institution had one year to prove they were worthy of remaining accredited. This time, the team replaced the list of recommendations with 14 “deficiencies” that built off the former.

The July press conference revealed only two of those recommendations were adequately met. As a result, CCSF’s accreditation was revoked, but the college would be allowed to remain open and accredited for a year while it appealed the decision.

California Community College Chancellor Brice Harris promised change would come to the much maligned administration of City College, and it started at the top. Within a week, Harris effectively suspended the seven-member board of trustees and elevated Robert Agrella, the recently retired president of Santa Rosa Community College in their place as a “special trustee with extraordinary powers.”

“I’m convinced that the current City College Board of Trustees cannot do this on their own,” said San Francisco mayor Ed Lee. “That’s why I emphatically support state Chancellor Harris’ recommendation that we give a special trustee full authority to make the decisions on the behalf of City College.

Agrella had already been handpicked by Harris as the (ordinary) special trustee to CCSF in November 2012, to address the school’s myriad of fiscal problems identified by the ACCJC. Annual budgets are not approved on time, sometimes not until a third of the way into the fiscal year. And before the end of 2012, a loophole allowed students to register and attend classes without paying, costing the college an estimated $8.5 million over several years.

The former president of Santa Rosa Community College is now in charge of saving the nine-headed Hydra of campuses from closing and nearly 80,000 students from relocating. It’s a herculean task, even according to Agrella himself.

Currently, CCSF uses a database for payroll, financial and student records called Banner. It’s used at Citrus and many other education institutions for the same purpose. The ninth generation of the software was released in 2011, but the Banner system at CCSF is in its first generation—so old, you can’t even Google it—and Agrella says it will take a year and a half before the database is fully upgraded.

“The biggest obstacle [to regaining accreditation] is probably change,” said Citrus College vice president of student services Arvid Spor, who was dean of enrollment services at El Camino when Compton College lost its accreditation in 2006. “People have to change the way they used to do their work to the way they need to work in order to comply with the standards set up by the accrediting commission.”

But Agrella has to deal with a campus community that doesn’t exactly embrace change with open arms. During the board of trustees meeting at which his position was accepted, a bizarre protest took place where students briefly took over and summarily rejected the special trustee position. The campus community at large is pointing the finger at the accrediting commission for their alleged deficiencies, rather than the institution.

“I strongly believe that this decision is unwarranted,” said Sara Bloomberg, editor-in-chief of CCSF student newspaper The Guardsman. “The decision is very political on behalf of the accrediting commission. I believe the City College community did everything that it was told to do and made a lot of progress towards the goals that were set as far as addressing all of the recommendations . . . and it wasn’t good enough as far as the commission was concerned. It doesn’t make any sense.”

However, the allegations of Bloomberg and the campus community were apparently not without merit. In April, the California Federation of Teachers lodged a complaint with the Department of Education against the ACCJC’s accrediting procedures.

The DOE sided with the teachers on Aug. 13, agreeing that the commission did not follow its own policies on including faculty on evaluation teams (the 2012 show-cause team had only one faculty member out of 17) and federal policies on creating conflicts of interest (Peter Crabtree, another member of the 2012 evaluation team, is the husband of Barbara Beno, the ACCJC president).

Additionally, the DOE found that the commission’s practice of morphing 2006 “recommendations” into 2012 “deficiencies” was not acceptable. In a letter to Beno which detailed the ACCJC’s shortcomings, the DOE wrote “in order to avoid initiation of an action to limit, suspend, or terminate ACCJC’s recognition, ACCJC must take immediate steps to correct the areas of non-compliance.”

However, the threat of an accrediting commission losing its own accreditation was not enough for the DOE to overturn the ACCJC’s decision to come down on CCSF.

“CCSF was unsuccessful in showing cause why its accreditation should not be removed,” DOE spokesperson Jane Glickman wrote in an email to Bay Area radio station KQED. “The Department does not have the authority to reverse any decision made by an accrediting agency.”

Since the DOE effectively washed its hands of the situation, San Francisco City Attorney Dennis Herrera has filed suit against the ACCJC in an attempt to nullify the commission’s decision to revoke the college’s accreditation. On Aug. 21, the Joint Committee on Legislative Audit voted for a review of the commission as well.

In the meantime, City College faculty, staff and students are scrambling to do what they can. They remain hopeful—but the clock is ticking.

“We’re all taking this very seriously. I’m hopeful that the situation—as grim as it seems right now—will turn around,” Bloomberg said. “The school has not lost its accreditation yet.”